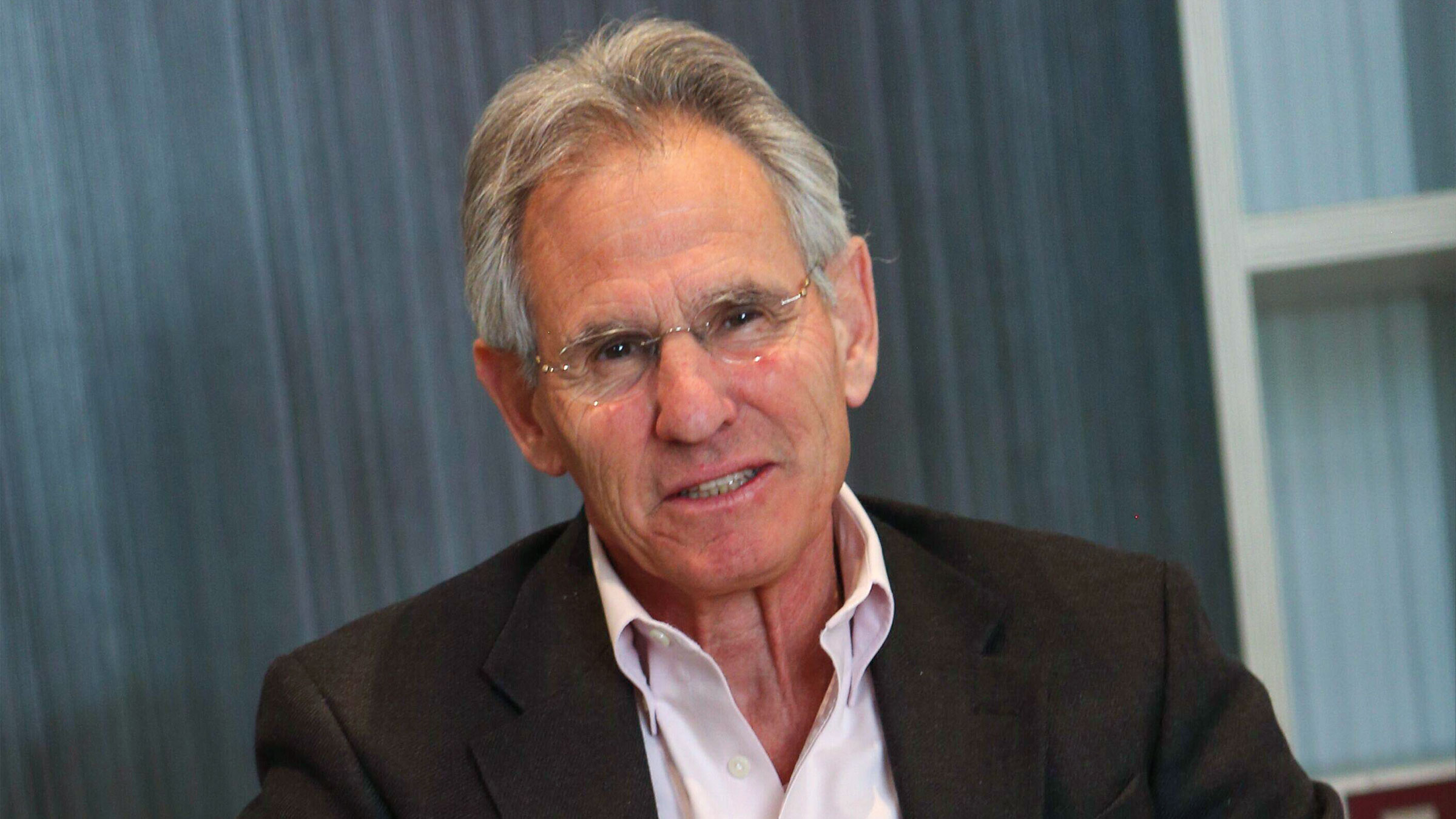

Melvin McLeod: When did you start practicing meditation?

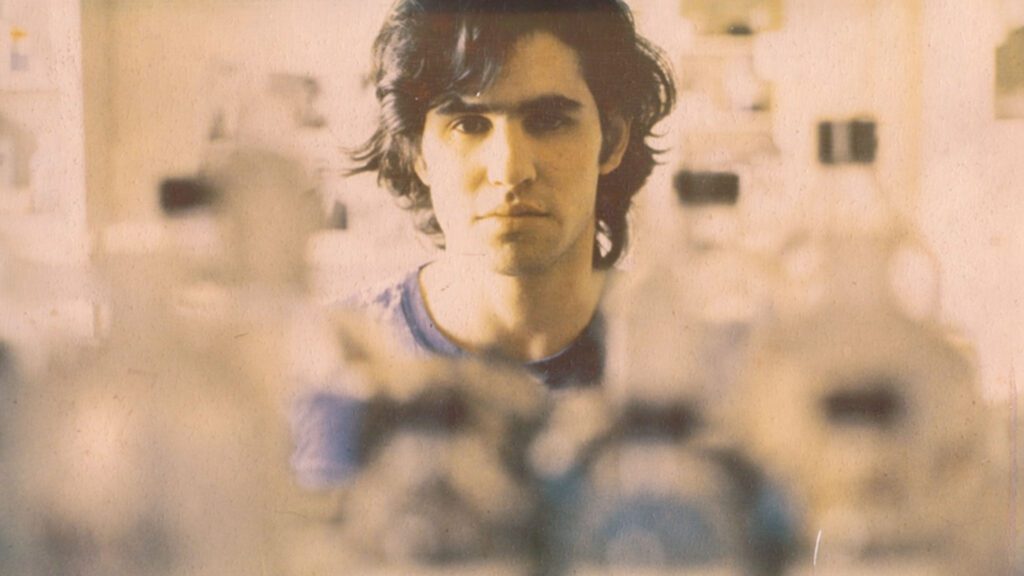

Jon Kabat-Zinn: My first experience of formal practice—or even learning about it—happened one day in 1965. I was a molecular biology student in the laboratory of Salvador Luria, a soon to be Nobel Laureate, and I was depressed out of my mind over the Vietnam War. Walking down the halls of MIT, I saw a sign on the wall: The Three Pillars of Zen: A Talk by Philip Kapleau, at the invitation of Huston Smith, who at the time was a professor of philosophy and religion at MIT. I had never heard of either of them, but there was something about that sign that drew me in—perhaps it was the iconography of the three pillars, or the mystery of the word “Zen.”

MIT is a community of thousands of people, but it turned out that only about four people showed up for the talk. I was one, and Kapleau’s talk took the top off my head. He told a personal story about how, as a reporter at the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal, hearing the testimony about the Nazi atrocities at an unimaginable scale had had a profound effect on him. Somehow, after that experience, he wound up sitting in a Zen monastery in Hokkaido, the northernmost island of Japan, in the wintertime.

He arrived with all sorts of body problems, including ulcers. The monastery had no central heating, so he was meditating in the freezing cold. He was highly motivated and committed fully to adhering to the rigors of the practice, no matter what. And, as he said in his talk, after six months of this intensive practice under such difficult conditions, his ulcers disappeared, and he felt like his mind had recuperated from the trauma of the Nuremberg trials. He had found himself, in a certain way.

At that moment, the thought ran through my mind: “This is what I’ve been looking for my whole life.”

Why do you think that is?

I think that it is because, as a child, I grew up with a father who was a highly accomplished scientist at Columbia University Medical School, and a mother who was an extremely committed and prolific painter who seemed to notice things in the visual field in ways most people didn’t. Sometimes I say she saw with eyes a lot like Monet’s. Walking along the street, she would comment excitedly on shadows, reflections in windows or on water, or on the surfaces of cars, and so forth. She painted in a range of different ways and explored a lot of different modalities—not just paint—in her artwork. Monotypes were a favorite of hers. And looking at her many sketchbooks when she was in her late nineties, she would revise her work with stronger lines, saying she just was not bold enough when she was younger.

So, I grew up living within these two cultures: father a scientist, mother an artist. As a result, I somehow intuited very early on that there were different ways of knowing the world. There were approaches to understanding what was hidden and could be made apparent through rigorous, scientific investigation, and there was creative artistic investigation and expression that wasn’t aimed at verisimilitude or precise reproduction. Both were in my DNA in a certain way, and not just literally. Somehow, they were also in my heart. So, when I heard Kapleau speak, it struck me that what he was pointing to was what I’d been looking for my whole very short and at that point fairly underdeveloped life. I started meditating that night, and never stopped.

Yet I think the experience or reality that Philip Kapleau pointed out to you—that you then pursued in meditation—transcends both the artistic and the scientific background. It’s a third way that actually transcends any form of conceptualization.

I wouldn’t say transcends so much as includes. It’s a way of understanding that unifies different universes, so to speak, into a much larger whole. And I saw that instantly when I heard Kapleau recount his own experience.

The meditation practice that you speak of was offered in the framework of religion for thousands of years, specifically in the framework of Buddhism. Now, in modern society in America, that religious framework can be—for certain people—a barrier to accessing these practices and this wisdom. So, you made what I believe is a historic strategic decision to take the universal truths and practice out of the context of religion and present them more broadly and more accessibly. Would you tell us about when the light bulb went off for you that mindfulness is not inherently religious, and in fact could be much more beneficial and accessible when presented outside of the context of a foreign religion called Buddhism?

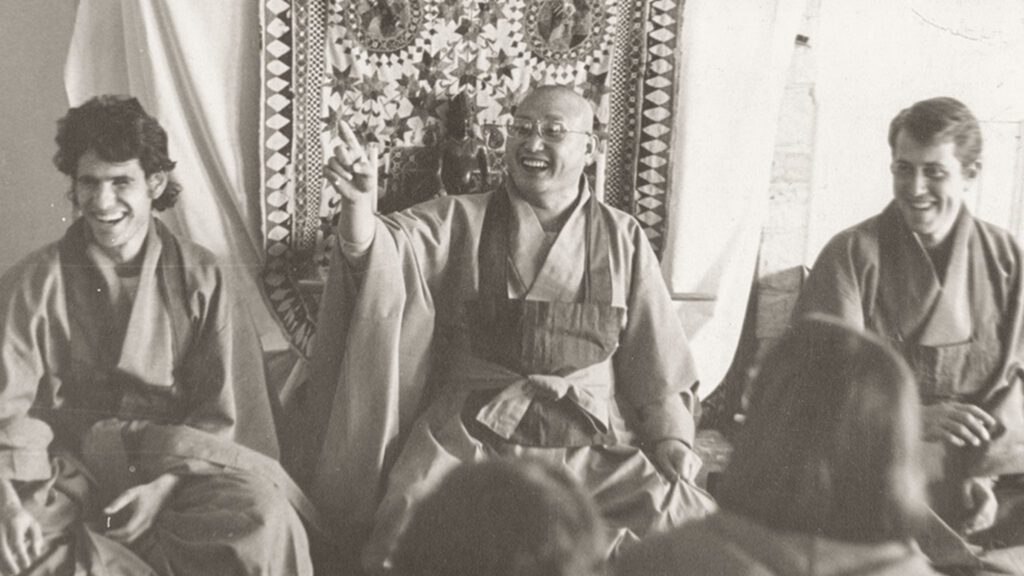

I think it was from the very beginning that I realized Kapleau’s experience had a universal resonance. For more than a decade before starting MBSR in 1979, I let these ideas percolate and evolve within my own practice and alongside a sangha of people I deeply cared about, practicing with teachers from both the East and the West who seemed authentic to me, including for several years the Korean Zen teacher Seung Sahn Seon Sa Nim, whom Stephen Mitchell wrote about in Dropping Ashes on the Buddha.

I was not interested in religion, but I thought, here’s something of intrinsic value that we can offer to people. I also had the thought at some point that the world would be a better place if everybody meditated. If everybody had a meditation practice, there’d probably be a lot less violence and aggression. There’d be greater well-being, greater happiness, a greater sense of agency, because tuning the instrument before taking it out into the world gives you the freedom to be in much wiser relationship to the forces, both inner and outer, that impinge on all our lives sooner or later, including stress, pain, and illness, to say nothing of greed, hatred, and delusion.

The first noble truth is the actuality of dukkha, which is usually translated as suffering but has many subtle tones to it. Dukkha really has more to do with suffering than it has to do with pain. If you differentiate pain from suffering, then there’s space. And that space can be very beneficial to learn to inhabit if you have had four back surgeries, tried all sorts of different narcotics to alleviate the pain, only to discover that your life is not working the way you want it to.

So, one of the insights I had early on, well before MBSR, was that under the right circumstances, pretty much anyone could benefit in one way or another from the kind of intentional fine-tuning that meditation and yoga might bring into one’s life. And at a certain point in asking myself what my own karmic assignment might be, the idea arose, why not see if it might be possible to bring meditation into medicine?

How did you make the leap to look at mindfulness practice in a medical framework, oriented toward benefiting people suffering physical and mental ailments?

Between 1976 and 1979, I was working in a lab in the Anatomy Department at the UMass Medical School, doing molecular and cell biology research. I took the lab job because it came with an opportunity to teach (and learn) gross anatomy along with (and usually only one step ahead of) the medical students. As a yoga teacher, that was a phenomenal opportunity for me. But that said, by 1979, as I was turning thirty-five, I was well aware that this was not the long-term trajectory I wanted for myself.

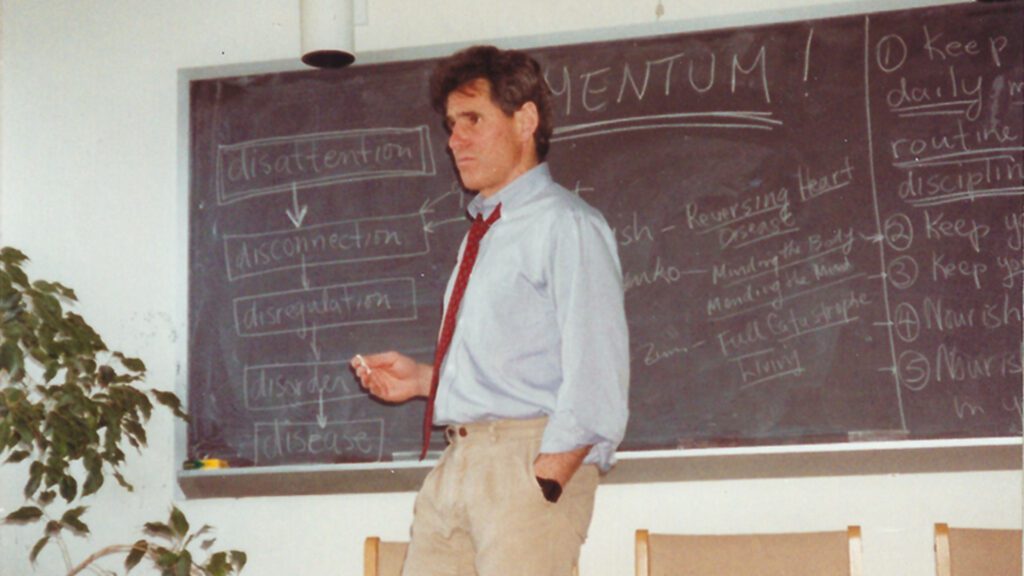

I reached a point during those years working in the lab as a post-doc where I was asking, “What am I doing with my life? What am I really supposed to be doing?” And so, in the third year, I began to talk to doctors in various clinics in the hospital, which at UMass at the time was in a different part of the same building as the medical school. I met with the heads of the primary care clinic, the orthopedic clinic, and the pain clinic and asked them simple things like, “What percentage of your patients do you feel you help?” And they told me, maybe 15 or 20 percent. And I’d say, “My god, what happens to the others?” And they said that they either get better on their own or they never get better.

A light bulb went off in my head. I said, “Do you think it would be of value if we set up an outpatient stress reduction clinic in the form of a course based on mobilizing the intrinsic healing capacities of human beings through fairly intensive training in mindfulness meditation and mindful hatha yoga, and you referred all the people you no longer knew what to do with?” All three heads of the clinics immediately thought of patients of theirs who might benefit from such a program.

So, I wrote a proposal to the hospital administration for a pilot outpatient program to test the feasibility and clinical effectiveness of bringing meditation and yoga into medicine. Part of it would involve carefully documenting outcomes and reporting them in the medical and scientific literature. I explained my own relationship to meditation, that I had been a student of the Korean Zen master Seung Sahn, as well as other meditation teachers over the years, and had a PhD from MIT in molecular biology. You could see the wheels turning in people’s minds: “He must know what he’s doing.” So, they let me do it, even though I had no professional credentials for working with human beings.

I felt quite trepidatious at first, especially because, right off the bat, the pain clinic referred a number of patients they categorized as “failures to treatment.” It turned out they were the best people to work with, because they had no place else to go. They had exhausted all their other options: back surgeries, many of them multiple times; as well as lidocaine injections targeting various “trigger points”; counseling and psychotherapy; headache clinics—the whole pain armamentarium, and they were still suffering. So, they were open to the proposal that, just as an experiment, instead of turning away from or trying to obliterate your pain, we’re going to put the welcome mat out for it. We’re going to investigate the experience of pain by attending to it carefully, with the sense that maybe you’ll be able to differentiate it from suffering. Because, while you’re going to have pain at one point or another in your life, how you are in relationship to it can make an enormous difference in terms of how much you are suffering.

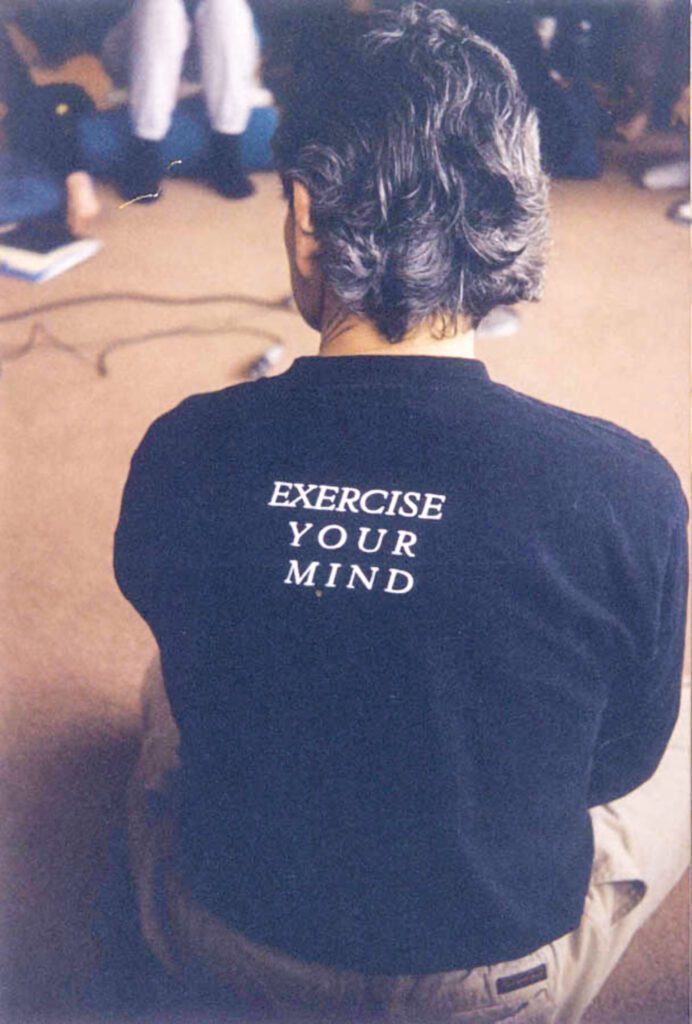

In this vein, when reporters and others ask me to give a one-word definition of mindfulness, aside from pure awareness, the other thing I say is relationality, because how you are in relationship to the actuality of experience matters and is potentially transformative and liberating. It is also a domain in which we all have considerable degrees of freedom and agency. But to access those degrees of freedom reliably, each one of us has to “exercise the muscle” of mindfulness through the ongoing and sometimes highly repetitive practice of paying attention systematically, in new ways. We have to learn the how of bringing this quality of attention to moment-by-moment experience through practice, through cultivation. So, that’s a little bit on the subject of how MBSR got started.

Can you tell me more about the structure of those first MBSR classes you taught?

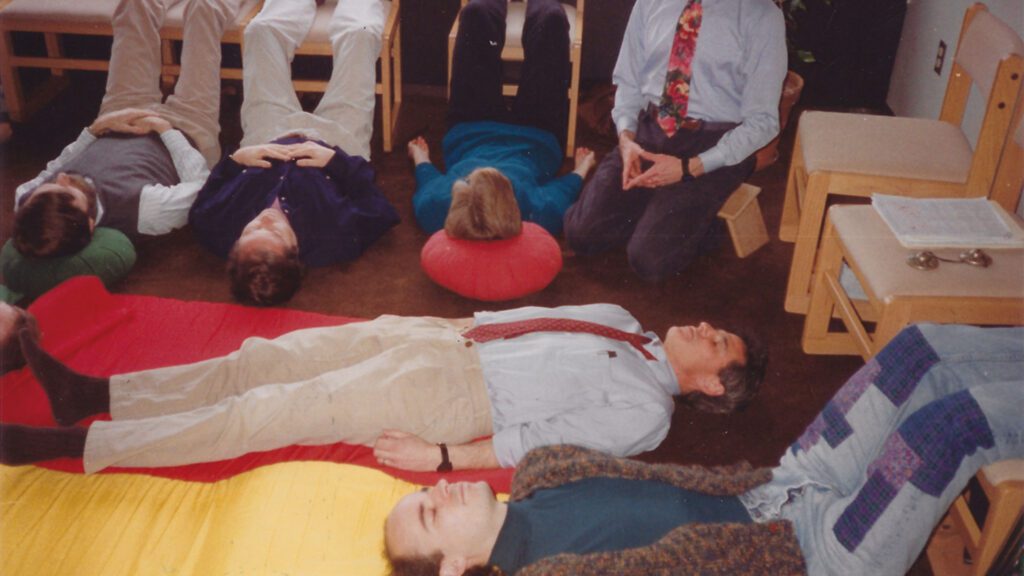

The heads of those three clinics sent me maybe fifteen or twenty patients for the first cycle of the program, which we later called Cycle Zero. Presently, the clinic—now online—is in Cycle 167. We had two parallel groups of patients. Each group attended two-hour classes once a week for ten weeks. It was only in year two that I included an all-day retreat session on a Saturday in the sixth week and made it an eight-week program, which since then has been the standard format of MBSR. I recorded a few guided meditations and guided mindful hatha yoga sessions on two cassette tapes. And because so many people had chronic pain conditions or disabilities, the first meditation was a lying-down meditation—what I called a body scan—which I developed out of my experience teaching the corpse pose in yoga and from an intensive retreat I sat in the early seventies in the tradition of U Ba Khin and S. N. Goenka, taught by Robert Hover.

The homework in week one was to practice just the body scan six days a week, using the tape for guidance. When people came back for class two, the effects the majority of them were reporting were remarkable in a multiplicity of ways. People began to discover aspects of their being that they had pushed into some corner and ignored. They began to reinhabit the body and trust the mind. Because we sat in a circle around the room, they could listen to each person who spoke about their experience and see that everybody was suffering in one way or another (we never use Buddhist terminology, such as dukkha or dharma). So, they’d realize, “Oh, my suffering is not the only form of suffering. I certainly wouldn’t want to have what that person has. Maybe I can find a way to live with what I have.”

So, then the question becomes, how to do that. You are invited to suspend all the judging and reacting as best you can and simply trust the practice moment by moment by moment. We frame the practice as a kind of laboratory. You investigate what happens when you’re doing the body scan, and you come to the most problematic part of your body, the place where there is usually significant pain or discomfort. You are invited to explore opening to it with interest and curiosity, even befriending it perhaps a bit in the moment—as opposed to contracting around it or running away from it.

That direct investigation of the unwanted includes what is happening in the mind at that moment. What thoughts are present? What emotions are present? What are the actual nociceptive sensations in the body? And then you can investigate by taking a direct look: In the midst of all of this, is my awareness of any of it suffering in this moment?

All of a sudden you discover that there’s a hidden but readily accessible dimension called “awareness,” within which experience can be held and known in a way that’s intrinsically and immediately free—though initially not for long, because we drop back into not being so aware and falling more into thinking and emotional reactivity. But then, in any moment, we can realize that and intentionally move back into awareness. Attention and intention working together in a yin-yang kind of synthesis or melding that people begin to recognize and work with as part of their practice.

Would you say MBSR empowers practitioners? It seems like the clinic encourages people to realize their own capacity for awareness and, therefore, relief.

Absolutely. Participants learn much more from their own ongoing engagement in practice than from the MBSR teacher. And perhaps this is the hardest part of being a skillful MBSR teacher: You can’t teach MBSR from a written curriculum, or book, or protocol, not even from Full Catastrophe Living, which maps out the entire MBSR program and the background for it. As an instructor, you have to be fully embodied in the practice yourself and, to whatever degree possible, teach the curriculum out of your own experience and agency, while still being true to the structure and spirit of the MBSR program as mapped out in Full Catastrophe Living.

So, it’s not about any pretence on the teacher’s part to being special or having attained anything. No, as the instructor, I’m here with everybody else, with my own stress, pain, and challenges, warts, pimples, and everything. We are all human. We all are subject to pain, stress, and illness. We are all going to die. But the challenge is, before we die, can we be fully alive in this moment? Can we be fully awake? Including awareness of our basic interconnectedness with all things, with others, with nature, with life itself, with the planet? In that regard, compassion arises naturally and is inseparable from awareness. And in that frame, just taking your seat is a radical act of sanity and love.

When people are related to in this way, through the being of the teacher rather than merely through what is spoken, their individual and unique agency is recognized and honored. In medicine, you often give up your agency and are just supposed to follow the instructions of your doctor. But in MBSR, the practice and the entire framework of the program is liberative and empowering on multiple levels.

What was the next step you took after obtaining such positive results?

I knew from the start that reporting outcomes would be a huge part of the work. If we didn’t document what was going on in the room, it would just be a nice set of stories and anecdotes, no matter how much benefit participants experienced. But if we systematically gathered pre-, post-, and follow-up data on people’s medical and psychological symptoms, on their anxiety, their pain, on any changes in strength, flexibility, and balance in the body and/or in the mind, and reported our findings in the scientific literature—then, if the overall results were noteworthy and medically and psychologically significant, the program, which only much later became known as mindfulness-based stress reduction, or MBSR, might have a much larger impact beyond just what was unfolding in our medical center; it might spread around the world, driven by the compelling nature of the scientific findings and their clinical implications.

That turned out to be the case. The first paper reporting on the effects of MBSR for chronic pain patients was published in 1982. Tracking the number of papers on mindfulness in scientific literature over time, you can see there were maybe one or two or no papers on mindfulness published each year for the next twenty years. Then, starting around 1999, it started increasing exponentially, rising to about 1,500 papers in 2022. Now, it is perhaps starting to level off, as all exponential phenomena have to at some point. Since 2010, a new scientific journal called Mindfulness has been publishing a great many of these studies, in addition to other top-notch journals. So, it’s become a legitimate scientific field to study meditation, not just in medicine, but also in psychology, in neuroscience, and all sorts of other domains.

This is just one of many indicators that mindfulness has moved into the mainstream. At what depth? That’s a whole other question. The heart of mindfulness is nondual awareness, the practice of prajnaparamita, translated as “wisdom beyond wisdom” by Kaz Tanahashi. I am not sure that every MBSR teacher would even recognize the word “prajnaparamita,” or know much about the Buddha’s teaching of mindfulness within the framework of the four noble truths and how powerful and germane those dharma teachings are to the world we are inhabiting today. But it is certainly advisable, actually essential, to investigate these domains in support of one’s own practice and teaching of MBSR and mindfulness more broadly.

In the Chan/Zen tradition of Tang and Song dynasty China, the articulation of this nondual practice was shared with the world through stories, koans, and other remarkable methods. While you can’t teach any of that in MBSR, as an MBSR instructor, it is important that you know it in your bones, through your own studying of books and learning from experienced teachers, as well as through your own practice; it is important that you embody it in your own unique way, that you breathe it.

It is axiomatic that in order to teach mindfulness, never mind MBSR, you have some kind of affinity and intimacy with this dharma, which is in essence both universal and infinitely deep. That intimacy is cultivated through both practice and study, along with attending periodic retreats with skilled meditation teachers.

When you started with just fifteen or twenty people suffering from physical pain, did you see MBSR as the first step in ultimately spreading mindfulness to millions of people like it did?

I saw it from that first moment when I was motivated to write scientific papers, documenting what was happening. Partly because of my upbringing, I understood in some deep way how science works and how you can create new fields if you have interesting evidence. I knew the evidence didn’t have to be totally conclusive at first. It just needed to be suggestive enough that other people would be inspired to devote some of their own precious time to investigating it in their labs or clinics, perhaps because it might be helpful or useful to their patients, or even in terms of their own careers. I was happy to see a range of positive motivations contribute to the growing interest in mindfulness.

After a while, of course, it became self-regulating. It’s not like I’m leading this movement. I see it as a self-actualizing, noncentric flowering of what I would call universal dharma in the world. To catalyze that kind of unfolding was the intention from the very beginning. And hopefully, what some are calling “the mindfulness movement” is continually evolving to be maximally relevant in a world that is changing incredibly rapidly.

The words meditation and medicine sound a lot alike, and they actually share the same deep etymological root. This fact made it feel like the field of medicine and health care was the perfect environment in which to offer meditation to people who were outpatients at the hospital, as a complement to whatever treatments they might be receiving, especially for those with chronic conditions, such as pain, that required learning how to live with and modulate them because they were not necessarily going to go away.

That said, there are many other places in society besides hospitals where introducing mindfulness practices can also be beneficial. One is schools—and I would say, at all levels, from kindergarten to graduate school. From an early age, we are going to need to know how to effectively ground ourselves in our analog bodies and minds and hearts, especially in the face of the ever more addictive dominance of phones and screens in our lives. This is even more important with the dawning of AI and its exponential integration into seemingly everything digital. As a species, we are going to need a much deeper appreciation of our analog genius, which we have barely scratched the surface of, and learn how to inhabit it fully as our default mode, our ground state, our original nature as human beings. Let’s not be so quick to abandon our analog beauty and genius to the digital merely because the latter is so seductive and addictive. It also comes with huge risks and major toxicity.

I’d like to suggest there are two aspects to mindfulness, although it is considered one practice. The first part could be called concentration: stabilizing, focusing, and quieting the mind. Once the mind is sufficiently quiet, the second aspect involves observing reality in an undistracted, clear way in order to see its true nature.

Mindfulness is sometimes understood as simply the first part of the equation—quieting, stabilizing, and focusing the mind—and many critiques of mindfulness stem from this partial understanding of the practice. But to me, the real payoff comes from what one sees when applying a focused, undistracted mind to the nature of reality—deeply examining one’s own being, the reality that one experiences externally, and the roots of suffering. The insight we can develop by applying a stable mind to looking clearly at reality is the true transformative power of the practice.

Agreed, except that’s a rather dualistic framing of it. It is important to remember that MBSR is only eight weeks long, and participants are often not motivated by the same reasons as people who attend Buddhist retreat centers to deepen their understanding of the dharma. So, without any reference to Buddhism or dharma, the MBSR teacher has eight weeks in which to offer a taste of the boundless spaciousness of awareness as both a reliable refuge in the timeless present moment, and as an ongoing practice not separate from everyday living. As we say in MBSR, “the eighth week is the rest of your life.” That eight-week trajectory presents a range of challenges. And this is another way in which the nondual Zen approach becomes essential to the teaching of mindfulness.

If people get off on the wrong foot with their meditation practice, they might still carry that misunderstanding decades later—believing meditation is about getting somewhere else, having some special experience, or trying to ignore, eliminate, or transcend pain. But the invitation of mindfulness is to drop into the actuality of experience, opening to this moment just as it is, with things exactly as they are, and then, to whatever degree possible, seeing if you can be at home with what is unfolding. In all likelihood, you will discover that your equanimity and nonreactivity are very limited, that you’re going to react virtually instantly with all sorts of thoughts, emotions, contractions in the body, with impatience, with aversion.

You might think, “Why am I meditating? I’m sure this isn’t what I’m supposed to be feeling.” Yet this is exactly what you’re supposed to be feeling. Why? Because the curriculum here is that you are staying open to feeling and recognizing whatever it is you are actually feeling. No matter how painful or disturbing it is, for at least a moment, seeing if you can hold it in awareness as a parent might hold a child, with pure love. That moment of awareness is a moment of liberation. It’s not like you have to sit for fifty years to taste moments of liberation. But it helps if you come to see life itself as the practice, and every moment as a gift.

If MBSR is not taught from that point of view, it’s not MBSR; it’s more like cognitive behavioral therapy. But if it is offered in that way, then the meditation practice itself does all the work. The dharma does all the work, and you don’t have to worry about the outcome.

And one more thing. MBSR, as well as many other mindfulness-based programs, such as MBCT (mindfulness-based cognitive therapy) and MBCP (mindfulness-based childbirth and parenting) has been the work of hundreds if not thousands of dedicated practitioners and researchers all around the world. I want to acknowledge, honor, and express gratitude to all of them, and in particular, those who work at the Center for Mindfulness at UMass Memorial Health, at the Brown University Mindfulness Center, and the University of California San Diego Center for Mindfulness, as well as all those teachers and researchers around the world who have trained with or collaborated with those centers.