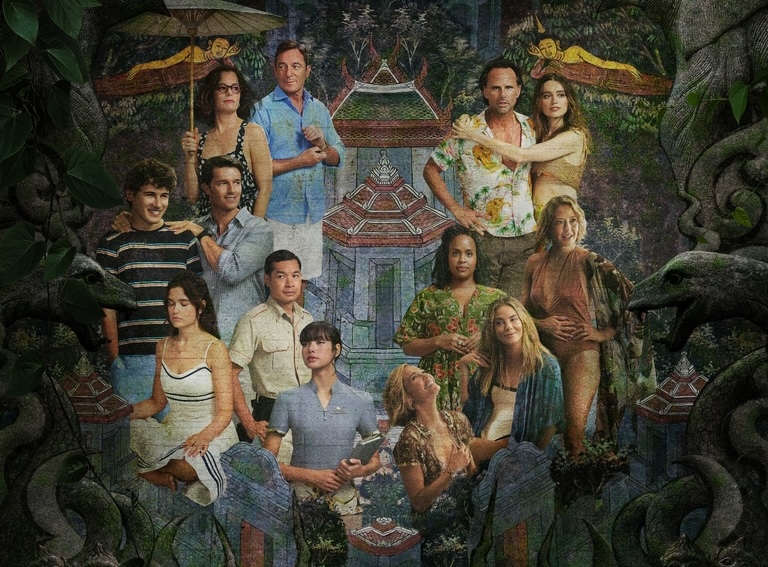

Buddhism is often viewed in the West through a simplistic lens, usually defined by meditation, mindfulness, and a sense of calm detachment. The third season of writer-director Mike White’s The White Lotus did get some aspects of Buddhism right, and some, well, less so. Let’s have a look at it all.

Sometimes Hollywood Gets It Right!

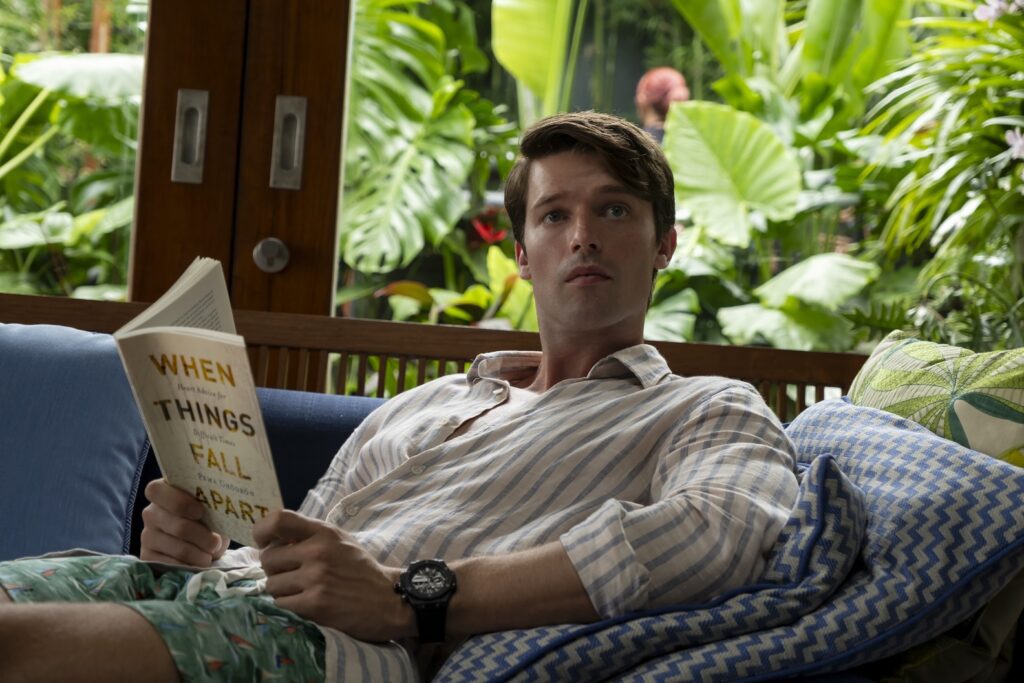

The character of Piper Ratliff is a great place to start. The young college student’s interest in books about loving-kindness, a fundamental Buddhist practice, reflects a core Buddhist concept. Loving-kindness (known as metta in Pali) involves the practice of cultivating friendliness and the aspiration for all beings to be happy. This is a positive and accurate depiction of the teachings of the Buddha. Similarly, while there are some inaccuracies (like showing meditators practicing with palms up, not generally a default Buddhist approach), the show’s depictions of meditation and offerings to local deities are rooted in Buddhist practices, as these are found in some schools of Buddhism. There’s a scene where Chelsea hands Saxon Ratliff When Things Fall Apart by Pema Chödrön, as he’s beginning to explore meditation and look inward. We later see him reading the book, suggesting he’s genuinely curious about the teachings, but when they talk about it, their conversation has nothing to do with what Pema actually writes. (Lastly, Saxon is seen reading Chödrön’s book Start Where You Are, toward the end of the show.)

One great moment in the series is when Luang Por Teera, the fictional Buddhist abbot of the monastery whom Piper and her family have visited, explains that we all have the potential to do harmful things, like killing, because emotions like anger and aggression drive us. He also stresses that any kind of violence harms both the victim and the perpetrator. And he’s spot on! The antidote he offers when harmful emotions arise is to sit down with your feelings, which seems to refer to the practice of mindfulness. However, it’s important to note that mindfulness is not the end goal but a means to an end. It is frequently presented merely as a technique for reducing stress or improving focus. In contrast, within the Buddhist context, mindfulness is an integral part of meditation practice and the development of wisdom. It’s not just about being present; it’s about seeing things as they truly are, free from attachment, aversion, and delusion.

There’s another scene where the abbot talks about anxiety, noting that most of us crave solid ground beneath our feet and are quick to settle for temporary solutions. But since these solutions are often rooted in confusion, they tend to generate even more anxiety and suffering. Everyone runs from pain toward pleasure, only to find more pain when they get there, as the great master Shantideva would say. The abbot ends with a somewhat vague yet comforting conclusion for an audience: that there’s no resolution to life’s big questions, so we should just be patient and accept that. But if there were truly no resolution, the Third Noble Truth — the cessation of suffering, and the path leading to it — would lose its meaning, even on a relative level.

At the end of her stay at the monastery, Piper spends a day complaining about the food and discomforts, admitting that she’s attached to her comforts and pampered lifestyle, even though she knows she shouldn’t be. In my experience, this perfectly reflects what often happens with many Westerners who approach Buddhism and stay in Asia. In general, food at retreat centers or monasteries is extremely simple, sometimes even boring for foodie palates used to variety and bold flavors.

The Buddha emphasized non-violence in his teachings, making it clear that avoiding harm isn’t just about being empathetic toward others; it’s also about not making a mess for ourselves. That’s why the show gives us the case of Gaitok, the hotel security guard who is constantly encouraged to be more aggressive or even violent. But thanks to the influence of his Buddhist roots, Gaitok maintains that being violent isn’t something that actually brings any real satisfaction. Basically, he’s saying, “Yeah, I could do it… but let’s not pretend it will feel good.”

The contrast between Gaitok’s values and Mook’s worldly desires becomes clear during their conversation. Mook is initially interested in him when she believes he’s advancing, but when he rejects the idea of seeking status and wealth, she expresses disappointment, revealing a clash between his Buddhist values and her focus on material success. In a way, she becomes a kind of Mara figure, tempting him, as Mara did with the Buddha with everything that society considers important: money, power, recognition, while he chooses humility and simplicity instead. This reflects the Buddha’s journey to enlightenment, where Mara represents the inner and outer forces that obstruct awakening. Buddhists don’t put stock in an external evil like Satan, so if one had to name a “Buddhist evil,” it would be our own habitual patterns. It is worth mentioning that in the end, Gaitok gives in to these “temptations,” killing, rising in status, and ends up falling into this cycle, as he becomes the bodyguard of the hotel owner, Sritala Hollinger.

And, Sometimes…

The White Lotus misrepresents some aspects of the Buddhist view of reality. Although Buddhism is inclusive and friendly with other religions, one major inaccuracy is the portrayal of a Brahma statue in a Buddhist shrine, which is inconsistent with typical Buddhist practice and misleading in its blending of Hindu and Buddhist imagery. Additionally, the show uses the term “spirit” to describe a non-physical essence, whereas Buddhism focuses on the mind and teaches about the absence of a permanent self, spirit, or soul.

A particularly misleading moment arises when Luang Por Teera speaks to Piper’s father, Timothy Ratliff, saying that when we die, we are like a drop of water returning to the ocean. While this sounds poetic and comforting, it is inaccurate from a Buddhist viewpoint. The idea that “all drops will return to the source” can be seen as an oversimplification that undermines and contradicts the crucial Buddhist teaching of cause and effect, karma. Our actions have consequences, and what we do matters and shapes our future experiences and lives.

To reinforce this, I’d like to quote my teacher, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche:

Nowadays, many Buddhists feel embarrassed to talk about past and future lives. Some even go as far as saying that when we die, we will all dissolve into the atmosphere and become one. That is absolutely wrong! If that were true, then why not go rob a bank? Sell cocaine? Kill someone? Do whatever we want… We don’t do it because this illusion of karma and reincarnation does exist. And when it manifests, it brings pain. Even if it is an illusion, it is still painful.

Any Buddhist master from the Theravada tradition, as portrayed in the show, would have told Timothy that afflictive emotions, kleshas, lead to the creation of actions, karma, which keeps us trapped in the cycle of samsara, reborn again and again until we attain liberation. It’s funny how past and future lives are a tough sell for modern audiences, but questionable sibling vibes (brotherly incest) — No problem at all! Modern Western audiences often resist concepts like karma and rebirth, seeing them as mystical, unscientific, or incompatible with their worldview. Meanwhile, pop culture has become increasingly comfortable with exploring taboo themes, including morally ambiguous sibling dynamics, like with Saxon and Lochlan. It’s interesting how reincarnation is dismissed as implausible, yet audiences readily engage with narratives that push the boundaries of familial relationships without much hesitation. Though I’m sure this topic made some viewers a little uncomfortable.

The media often oversimplifies Buddhism, and Saxon’s character does an excellent job of portraying this limited understanding. He really leans into it, like when Lochlan asks, “But what if this life is just a test to see if we can become better people?” Instead of giving it any real thought, Saxon just laughs it off, brushing past the deeper meaning and showing he’s not too interested in looking beyond the surface. Concepts like karma and meditation are often simplified into catchphrases and self-help tools, lacking the deeper context they hold within Buddhist teachings. For example, karma is often reduced to the simplistic notion of “what goes around comes around,” without exploring the nuanced way our actions work in terms of intention.

What Everyone Thinks They Know About Buddhism (But Probably Don’t)

Sometimes, it’s easy to laugh at the common, and often superficial, misunderstandings of Buddhism that pop up in shows like The White Lotus. For example, when Piper’s mom, Victoria, asks, “Why are you Buddhist if you’re not Chinese? You were born a Christian in North Carolina!”—We can’t help but chuckle at how off-track that sounds! She also repeatedly refers to the Buddhist monastery and its inhabitants as a cult, showing how Buddhism is perceived by many people who have never been exposed to its basic teachings—teachings that, simply, focus on the mind, how to stop creating the causes of suffering, and recognizing our true nature. These funny moments definitely add something enjoyable to the series. But beyond the humor, we also have to recognize that how Buddhism is portrayed, both accurately and inaccurately, affects how people understand it.

The way the media presents different cultures and belief systems can shape how we see them, and when things are simplified or misrepresented, it can lead to misunderstandings. In the case of Buddhism, reducing it. It’s up to both the media and the viewers to understand that Buddhism, as a rich and complex tradition, can’t be fully represented in a TV show, especially one that mixes drama and spirituality, but that doesn’t mean it can’t spark meaningful curiosity and it’s still pretty fun to watch!